China’s satellite megaprojects are challenging Elon Musk’s Starlink

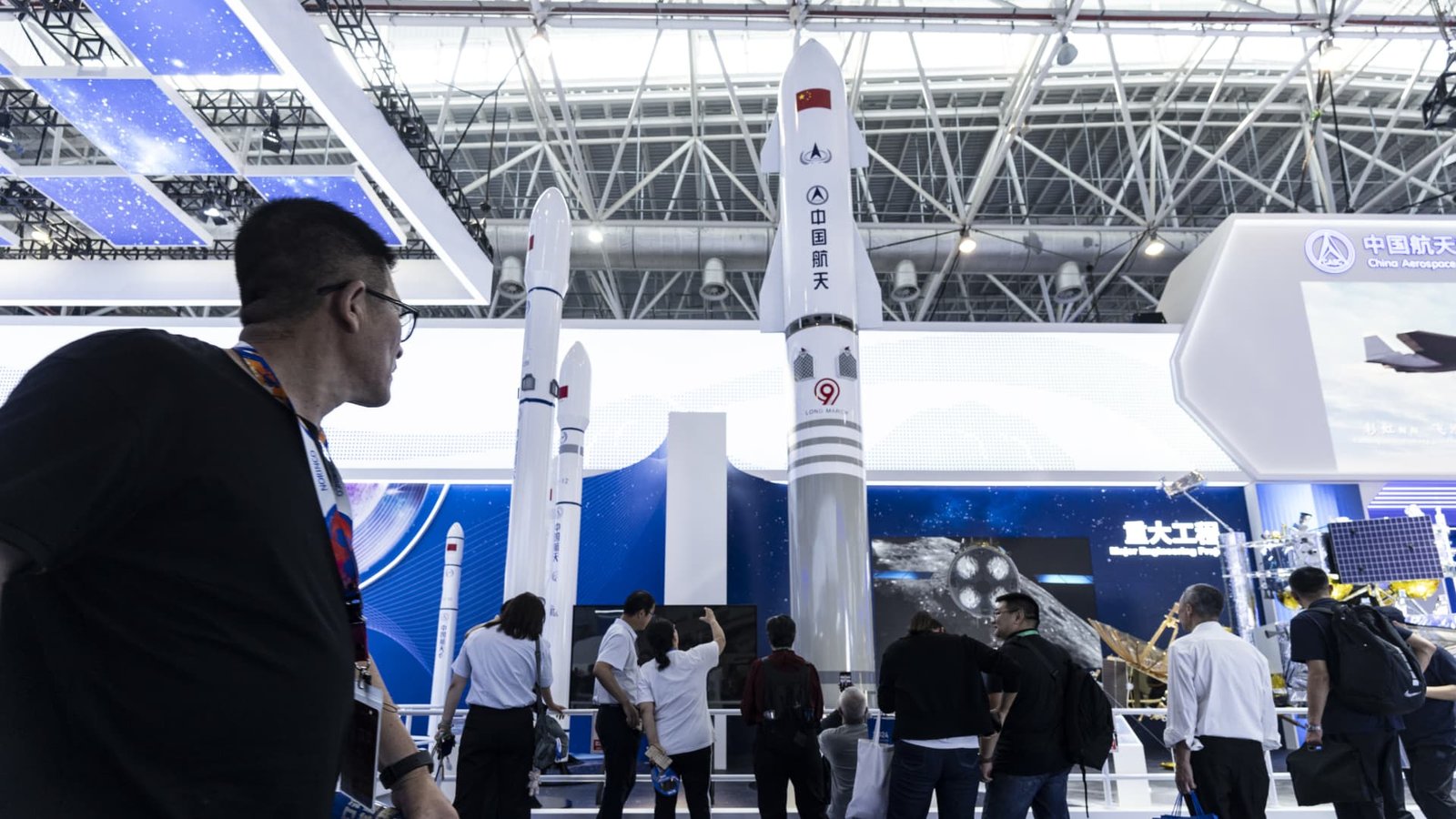

China faces a tall order in its efforts to catch up to Elon Musk’s SpaceX satellite service.

SpaceX’s Starlink already has nearly 7,000 operational satellites in orbit and serves around 5 million customers in more than 100 countries, according to SpaceX. The service is meant to offer high-speed internet to customers in remote and underserved areas.

SpaceX hopes to expand its megaconstellation to as many as 42,000 satellites. China is aiming for a similar scale and hopes to have around 38,000 satellites across three of its low earth orbit internet projects, known as Qianfan, Guo Wang and Honghu-3.

Aside from Starlink, European-based Eutelsat OneWeb has also launched more than 630 low earth orbit, or LEO, internet satellites. Amazon also has plans for a large LEO constellation, currently called Project Kuiper, made up of more than 3,000 satellites, though the company has launched only two prototype satellites so far.

With so much competition, why would China even bother pouring money and effort into such megaconstellations?

“Starlink has really shown that it is able to bring internet access to individuals and citizens in remote corners and provide an ability for citizens to access the internet and whatever websites, whatever apps they would like,” said Steve Feldstein, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

“For China, a big push has been to censor what citizens can access,” Feldstein said. “And so for them, they say, ‘Well, this presents a real threat. If Starlink can provide uncensored content either to our citizens or to individuals of countries that are allied with us, that is something that could really pierce through our censorship regime. And so we need to come up with an alternative.'”

Blaine Curcio, founder of Orbital Gateway Consulting, agrees. “In certain countries, China could see this as almost like a differentiator. It’s like: ‘Well, maybe we’re not as quick to market, but hey, we will censor the heck out of your internet if you’d like us to, and we’ll do it with a smile on our faces.'”

Experts say that while Chinese constellations won’t be the choice internet provider for places such as the U.S., Western Europe, Canada and other U.S. allies, plenty of other regions could be open to a Chinese service.

“There’s a couple of geographic areas in particular that might be attractive for a Starlink-like competitor, specifically one made by China, including China itself,” said Juliana Suess, an associate at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs. “Russia, for example, but also Afghanistan and Syria are not yet covered by Starlink. And there’s also large parts of Africa that aren’t yet covered.”

“We’ve seen that 70% of 4G infrastructures in the continent of Africa are already built by Huawei,” Suess added. “And so having a space-based perspective to that might sort of further build inroads there.”

Aside from being a tool for geopolitical influence, having a proprietary satellite internet constellation is increasingly becoming a national security necessity, especially when ground internet infrastructure is crippled during war.

“When it comes to the difference that Starlink technology has played in the Ukraine battlefield, one of the big leaps we’ve seen has been the emergence of drone warfare and the connected battlefield,” Feldstein said. “Having satellite-based weaponry is something that’s viewed as a crucial military advantage. And so I think China sees all that and says investing in this is absolutely critical for our national security goals.”

Watch the video to find out more about why China is building out these megaconstellations and the challenges the country will face.

https://image.cnbcfm.com/api/v1/image/108075396-1734037344513-gettyimages-2183848672-CHINA_ZHUHAI_AIRSHOW.jpeg?v=1734037421&w=1920&h=1080

2024-12-15 13:00:01